Participants Gain Skills to Effectively Evaluate and Describe Products

Pieces of dried mango rest on the bottom of a black opaque goblet. Next to it, another glass contains apricot jam. Leticia Cardoso Madureira Tavares, a second-year Ph.D. student in biosystems engineering, brings the glasses up to her nose one at a time to take a sniff.

She can easily recognize the aroma of the apricot jam. But the dried mango doesn’t quite hit the mark. She thought perhaps the tropical flavor she was detecting in a sample of honey she was analyzing was from fresh mango instead.

Honey varieties being studied

Orange blossom: gathered from California citrus groves, it’s light in color with mild citrus and floral notes.

Sage: gathered from many species of sage, its color can vary from golden to a dark hue and has a mild taste with a mix of fruity, floral and spicy notes.

Avocado: made from the nectar of avocado plant blossoms, its consistency is like molasses with its dark color and bold taste with earthy notes.

This sensory test was one of the first exercises Cardoso Madureira Tavares experienced as part of being on a trained sensory panel. She’s one of 11 people who are helping researchers conduct a descriptive analysis of honey.

Gaëlle Chanlot Delarue with the Department of Food Science and Technology assembled the panel this spring as part of a new research project to analyze and develop a profile of three honey varieties – orange blossom, sage and avocado – produced in California. In collaboration with the UC Davis Honey and Pollination Center, Chanlot Delarue and the team of researchers hope the profiles will help lead to a statewide and national standard to ensure consistency and quality in honey products.

Chanlot Delarue said the data collected from the sensory panel is critical for research.

“I told the panelists that they are the center of the study,” said Chanlot Delarue, who holds a doctorate in food science/sensory and consumer science. “There’s no study if they are not here. It’s really important.”

Cardoso Madureira Tavares, a self-proclaimed “foodie” and “honey fanatic,” jumped at the chance to explore the various characteristics of honey. She had previously participated in a consumer wine tasting panel, and this time she was eager to learn about the sensory evaluation process.

“This was a golden opportunity to indulge my curiosity and learn all about the incredible range of tastes that honey has to offer,” she said. “It's like a sweet adventure for my taste buds.”

Delectable training adventure

Trained sensory panels are a group ideally comprised of 8 to 12 people who are trained to use their senses to evaluate a specific product. They learn how to detect and quantify specific attributes, including flavor, aroma, texture and appearance. These panels are more complex and require a longer time commitment compared to a consumer panel, which is made up of individuals who voice their likes, dislikes and opinions about a product. Those sessions are typically quick and don’t require training.

The panelists for this honey study were required to commit to 13 one-hour sessions over the course of two months. Their task was to evaluate 12 different honey samples.

Learn about the nuances of honey

The UC Davis Honey and Pollination Center has a colorful honey flavor wheel with more than 100 descriptors, including lavender, blackberry and umami.

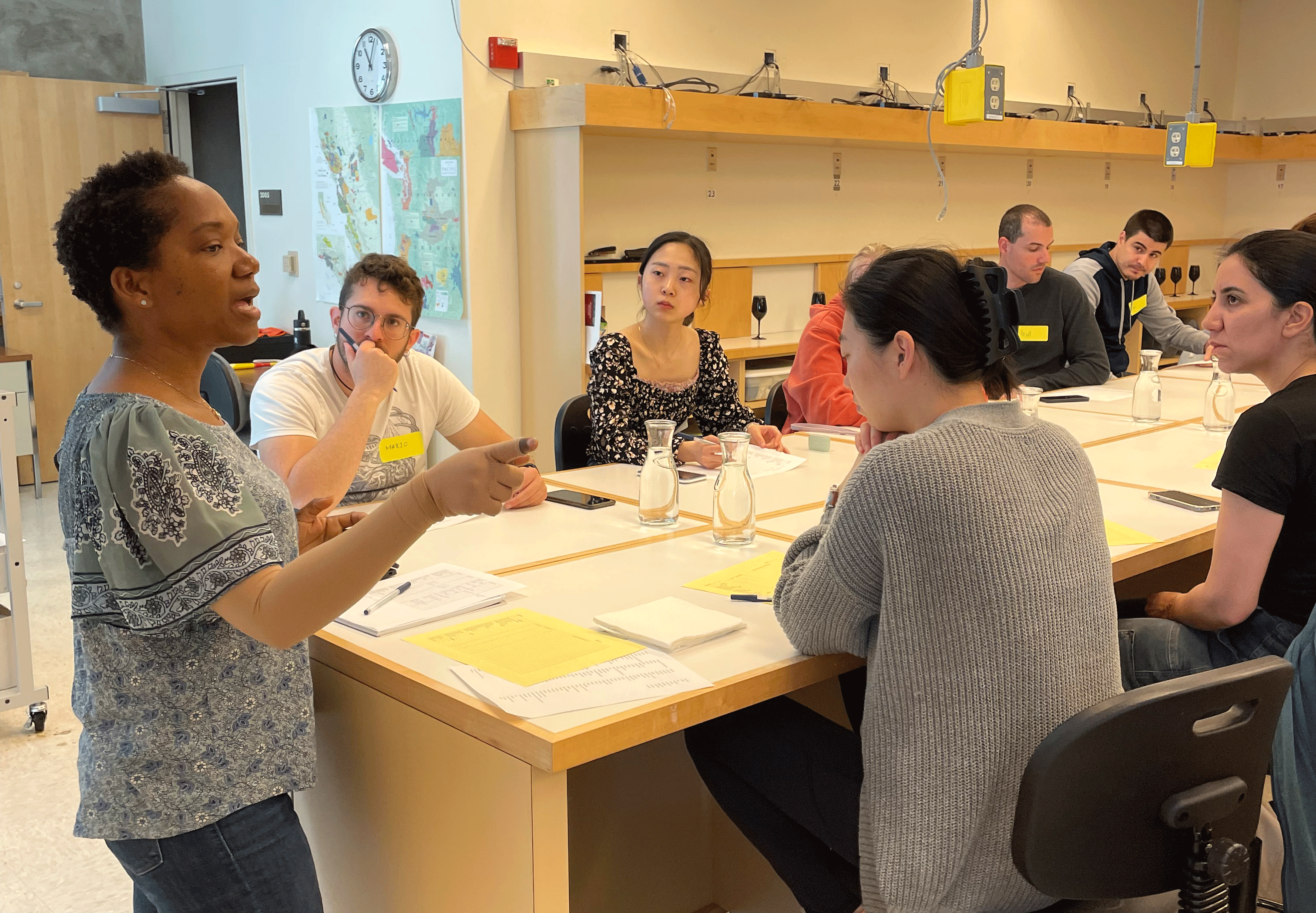

The first seven sessions were dedicated to training the group on how to develop and refine sensory skills. They met together as a group to go over specific terminology to describe sensory attributes of the honey samples. To recognize various aromas, a countertop in a sensory lab was lined with more than two dozen black goblets containing various items, including fresh jasmine flowers, apple slices, ground cinnamon, grass clippings and rose water. Panelists sniffed from each glass and took notes about their ability to reference those scents and/or flavors in the honey samples.

“It’s important to have a common language of attributes,” Chanlot Delarue said. “We work on what’s behind the word. If someone says, ‘This is grassy,’ or ‘This is spicy,’ we can begin to determine the specifics.”

The panel started off with a long list of descriptors and after deliberation were able to narrow down the terms. Guilherme De Moura Araujo, a postdoctoral researcher with the Department of Biological and Agricultural Engineering, said the training sessions were comprehensive and prepared him well for how to distinguish the subtle nuances between the different honeys, and how to work together with the group to express opinions.

“What surprised me the most was the different perceptions among the participants,” he said. “Some described aromas and flavors that I hadn't initially detected, but after hearing their insights, I was able to perceive some of those same aromas.”

By the end of the training, panelists were able to describe the attributes, detect differences in the samples and rate the intensity for every descriptor.

Sensory skills in action

The next step was putting their newly gained skills to work. The panelists spent six weeks evaluating the honey samples in sensory booths. Each panelist was alone in a quiet booth while trays filled with cups of honey were passed through a small window. The booths were quiet and had dim lighting (the brightness and color of the lights can be adjusted when testing products that could benefit from various surroundings). The idea is that the booth limits external factors so not to interfere with the sensory analysis process.

“The booth gives you a neutral and standardized environment that allows you to concentrate and that allows the measure to be replicated under the same conditions,” Chanlot Delarue explained. “You want a measure that is objective, without any noise, so to speak. You want to have something calibrated; if we are not in the same environment, the environment will impact your evaluation.”

Panelists smell and taste each honey sample and fill out a digital scorecard on a computer screen. For each one, they analyze the characteristics and scale the intensity of each attribute. They must repeat this step several times to make sure they’re getting a consistent assessment.

Once they’ve completed the evaluation, the panelists are done. For this study, participants were compensated for each session in the form of a gift card.

Both De Moura Araujo and Cardoso Madureira Tavares said they enjoyed participating on the panel and would consider doing it again.

“It was a rewarding experience to contribute to scientific endeavors and expand my understanding of sensory analysis,” Cardoso Madureira Tavares said.

De Moura Araujo, whose focus is agricultural health and safety, said while this study isn’t directly tied to his field of work, he finds the value in learning something new.

“I'm constantly exploring ways to ensure the well-being of those involved in agriculture and the quality of the products being cultivated,” De Moura Araujo said. “The awareness gained from being a sensory panelist underscores the importance of maintaining healthy, safe environments in agriculture, as these factors can impact the final products we consume, such as honey.”

Developing a honey standard

In addition to this sensory evaluation, Chanlot Delarue is also conducting a chemical analysis of the honey products. Among other things, it will measure amino acids to determine which compounds make up each of the varieties. Chanlot Delarue and the team of researchers will use the data from the sensory panel and the chemical tests to develop the honey profiles, potentially ensuring that honey products in the future meet consistent quality criteria.

“The main issue in the honey community is that people are adding compounds that aren’t supposed to be in the honey,” Chanlot Delarue said. “The study will help outline the profile of honey and will help develop a standard for California producers.”

She expects to present her findings later this year.

Media Resources

- Gaëlle Chanlot Delarue, Department of Food Science and Technology, gchanlot@ucdavis.edu

- Tiffany Dobbyn, College of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, tadobbyn@ucdavis.edu